The Basement of Babel

Fairytale Design Competition

Fairytale Design Competition

Winter 2018 / Blank Space Fairytale Architecture competition

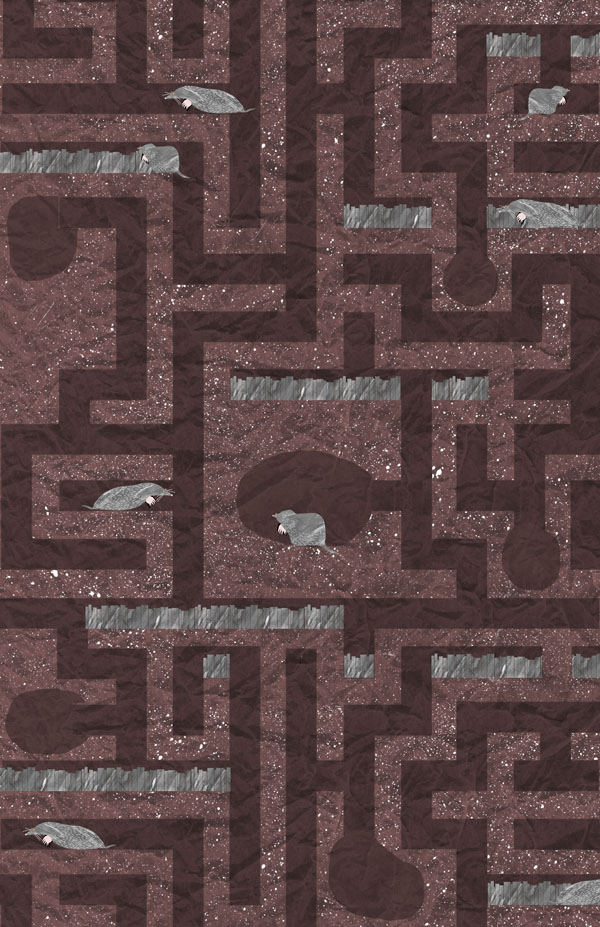

A competition hosted by Blank Space asked applicants to imagine, through images and text, one’s own architectural fairytale. The Basement of Babel imagines a library housing all the destroyed texts in history, stored beneath the ruins of Breugel’s Babel.

Images produced by Katie Kelly (ink, charcoal, photoshop); Accompanying story, and image editing by Ryan White

“The library, said the elder librarian, began small, though had been greatly expanded by the time the Xianyang library was destroyed by Yu’s troops, and its scholars were buried alive. The basement of Babel, he told Rarbily, stretched deep into the ground, as deep as the Tower of Babel had been tall.”

When the scrolls of Alexandria were incinerated and its walls toppled, all that was obliterated was brought here to be preserved through eternity. Every destroyed work, by action or accident, has contributed to the shelves of the Basement of Babel. Every forgotten text, rotting in its physical record, has been catalogued here. The libraries of Nishapur and Al-Hakkam II are here, destroyed in the name of secularism and ultra-orthodoxy respectively.

The god-fearers hold the higher burn count but the pragmatists have done their fair share in the name of ‘making space.’ You can find Kirchner’s paintings here too, with all those other ‘degenerate’ works torched by the Nazis.”

The librarians knew that in the land of Wippage the King had been waging a war against his neighbors, the people in the land of Moppage. There was a library in Moppage that held all of the military strategies that its Generals had proven successful from prior campaigns. The King of Wippage ordered this library destroyed and its scholars thrown into the very, very deep chasm, named for its great depth and the great height from which scholars were typically thrown.

Rarbily was sent to this place to bring its destroyed works to the Basement of Babel. While he was looking upon the library as it had once been, sorting the fragmented texts from the wholly perished, he had an idea: if he could convince the King of Wippage to stop the war, then the other libraries of Moppage might be saved from the destruction.

He burrowed a hole through the foundation of the castle. He knew that the king lived at the very top of the castle, in the highest of its parapets. He dug through floors and up through walls and ceilings from level to level. He kept climbing until he emerged into a tunnel, pre-formed, and followed its stinking path to the top of the castle and the King’s chambers. He emerged into a tiny pond, so tiny that it was really more of a puddle, encased by a white, slippery stone basin. This was where he found the King, hopping from foot to foot screaming at him. Rarbily was made to wait in the King’s bed chambers while the King conducted some noisy and unseen business that seemed to involve sitting over the pond.

When the King was done, he asked Rarbily who he was and what he was and how and why. Rarbily told him that he was a librarian from the Basement of Babel of the fabled, destroyed tower. This impressed the King who granted him an official audience to ask what he had come to ask. Rarbily told him he should stop his campaign and make peace with the King of Moppage, that more libraries would be destroyed in the effort.

The King didn’t understand, asked Rarbily to explain himself as his tailors sewed size 32 waist tags into his size 40s. Rarbily told him what he knew, that there had been stories destroyed, both real and imagined, that could make people forgive each other for their differences. The King still didn’t understand, so Rarbily explained:

If a person in Moppage wrote a story about life in Moppage, and a person in Wippage read it, the person from Wippage would feel a kinship with that person for having lived in Moppage through their imaginings. The King disagreed. The people of Moppage, he said, were stupid, and they had chosen the dumbest of the lot to lead them.

Rarbily asked the King who he had loved the most. The King didn’t have to think; the answer was easy to him. “My wife,” he said, “but she’s dead.” Rarbily asked if he missed her.

The King said he missed her immensely, that the vacant space her absence formed in his life could not even be filled by all the chocolate cake in the kingdom. So Rarbily said, the King of Moppage will feel just like you when you kill his family.

The King agreed to stop the campaign, but with a caveat: only if Rarbily could bring him the letters of his dead wife, which had been burned in a fit of rage years before.

Immediately, Rarbily set off for the Basement of Babel. It was not hard to find the letters, they were in the spot the elder librarian said they would be. He read the King’s wife’s letters and was surprised. They were not love letters at all, but an explanation of why she had left, why she could not go on living with him. But Rarbily had made his promise and returned to the castle. He gave them to the King who sat down on his bean bag thrown and read.

“I don’t understand,” the King said.

“What?” said Rarbily.

“They are gibberish. I can’t read them.”

Rarbily took the letters and examined them. He paused, knowing they would cause more pain. Impatient, the King raged and tossed his Fabergé eggs against the wall, then his omelettes, then his chickens, who glided safely to the floor, slightly annoyed.

“But don’t worry,” lied Rarbily, “I shall read them to you.”

Instead, Rarbily spoke of how much the King’s wife had loved him, how much she regretted leaving him, rejecting the love they’d shared. She even asked for his forgiveness.

The King was moved, his eyes drowned in tears, his face crinkled with pain. Distraught, the King threw himself down before Rarbily.

“I should have never chopped off her head,” wailed the King.

Rarbily inched toward the porcelain pond afraid.

“Yes,” said Rarbily, “a rash decision indeed, but you can learn a lesson and stop this war.”

The King looked up imploringly to Rarbily.

“Will I be forgiven?” asked the King.

“I’m not really sure, but it couldn’t hurt!” said Rarbily, trying his best to appear encouraging.

So the King called in his courtiers, who called in his squires, who called in his pages, who called in his runners who ran to call in his cavalry to escort his generals to the castle. The generals conceded to the King’s wishes and a hundred runners were sent to convey the message to Moppage that the war would end that night. The people rejoiced in peace.

Rarbily was exiled of course from the Basement of Babel for his thievery. Initially discouraged, he learned to find comfort in the literature and art that had been saved aboveground, those texts which had been handled with love and care, passed on and replicated, added to base of the tower that was knowledge.